Working With the Garage Door Up: Creative Technologist-in-Residence Kelin Carolyn Zhang on Design, Prototyping, and Creative AI

Kelin Carolyn Zhang’s approach to design is as transparent as it is exploratory. “Working with the garage door up” perfectly encapsulates the spirit of her residency at MFA Interaction Design: a process that brings students in early in the process and shares not only the polished final product, but the iterations, learning, and very human messiness that shapes it.

This residency program is an experiment in itself, a year-long open studio that blends practice, mentorship, and inquiry into the future of design—and the designer.

“After being a guest speaker and running workshops for our students over the last two years, we wanted to find ways for our students to work more closely with Kelin. We co-designed this residency with her, so that she could serve as an everyday resource and role model for creatives inventing joyful and inclusive products that leverage emerging tech.”

-Adriana Valdez Young, ixD Chair

For Zhang, whose background weaves together computer science, interface design, and AI-powered creative projects, the motivation for this residency is personal, and a natural extension of her existing design practice. “Design has always been apprenticeship-based,” she says. “You learn the most by seeing someone’s process up close—what works, what fails, and how they navigate through it all.”

Rethinking the Role of Designer

Zhang’s current practice sits at the intersection of technology and creative thinking, hardware and whimsy, and the multifaceted structure of the residency is built to reflect this. Each week, she creates a new prototype and shares it with students—not just the object or interface itself, but its backstory: the origin of her idea, debugging, and unexpected turns along the way.

The first prototype was inspired by a student: a physical Pomodoro timer* shaped like a padlock—encouraging the user to “lock in” for 25 minutes at a time. “When you close the lock, the timer starts,” Zhang explains. A simple idea, but a tangible one that touches on human behavior and motivation that returns to physicality in an age of countless productivity apps available on smartphones.

*A time management method developed by Francesco Cirillo in the late 1980s, in which a person uses a timer to work in 25-minute focused work sessions followed by short breaks. The name "Pomodoro" comes from the tomato-shaped kitchen timer used by Cirillo.

These weekly projects serve as open case studies focused on the very real practice of design.

As Kelin puts it: “I want students to see that prototyping doesn’t have to be perfect. That you can—and should—show work in progress. It’s more relatable and more instructive.”

To facilitate connection, Zhang holds open office hours and maintains a Slack channel where students can ask her questions directly and follow her work in real time.

“It’s a way to show students what’s possible,” she says. “These processes can be difficult to distill into a shorter class, but if they can see it unfold throughout a semester, it adds a different dimension to their education.”

From MIT, to Twitter, to an Independent Practice

Zhang started out at MIT, studying computer science. She quickly realized that she wasn’t interested in becoming a software engineer. “I was more drawn to how people interact with technology,” she says.

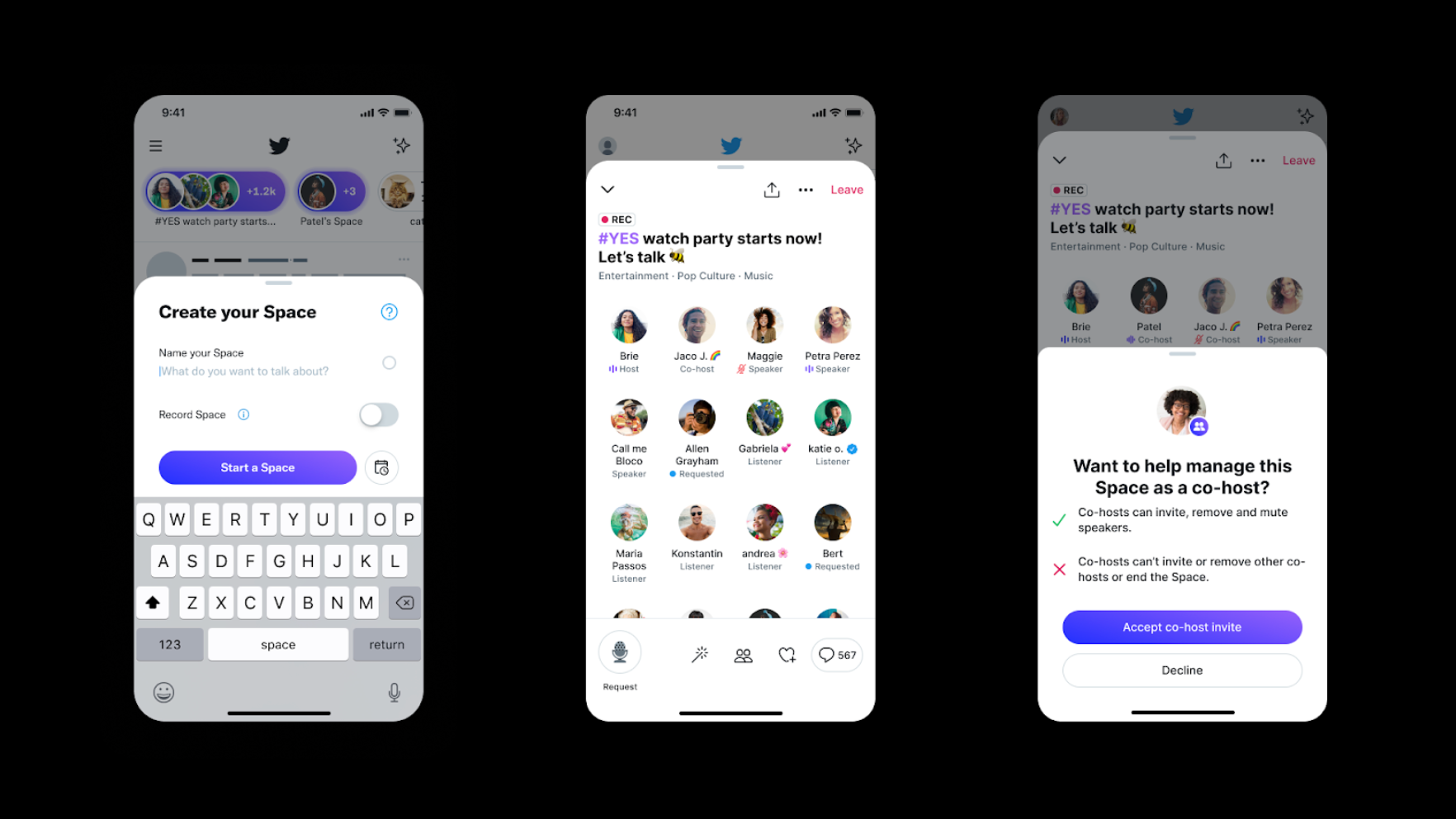

That interest took her to the design studio Ueno, where she spent four years doing interface and product design for clients like Apple, Google, Reuters, and Dropbox. After working on political tech during the 2020 election, she joined Twitter as a product designer, working on new interaction formats like Twitter Spaces. She stayed through the company’s acquisition, then left to pursue an independent design practice.

Brand & product work for Mobilize, the Democrats’ volunteer organizing platform

Product work for Twitter Spaces

It was around that time—late 2022—that she began exploring what tools like ChatGPT might mean for design. “It felt like a medium that was alive and constantly changing,” she recalls. “And I remember thinking, this is going to change everything about how designers work.”

Designing in the Age of AI

For Zhang, AI tools don’t replace creativity—they expand its reach. In January 2023, she set a goal for herself: to reinvent her design process in an AI-native way. This shift included using AI to build software directly, instead of drawing static mockups of the screen.

“I realized that I could ask the model endless questions in a way that was different from any other learning model. That lowered the barrier to entry in a huge way. It let me pursue ideas I might have otherwise talked myself out of.”

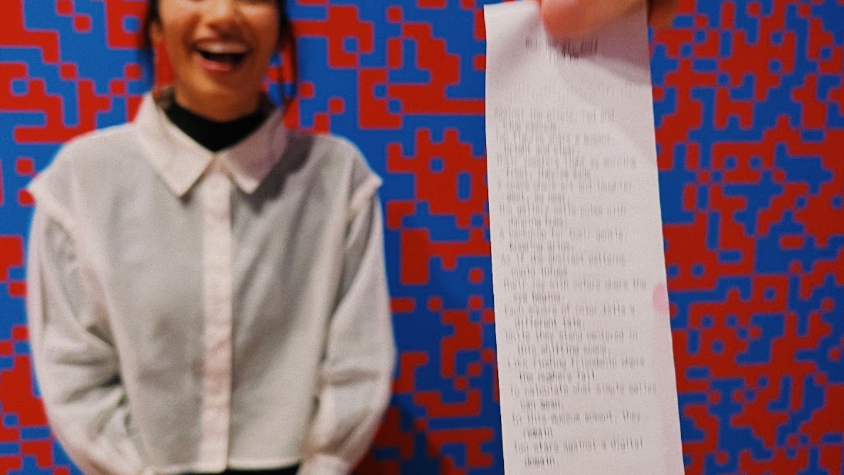

One of those ideas became Poetry Camera: an instant camera that prints poems of what it sees, built in collaboration with Ryan Mather. It’s an inspiring example of what’s possible when design, code, and curiosity intersect.

It’s exactly this kind of thinking Zhang hopes to spark during her residency.

“Design is changing so much—especially software and interface design. The old rules don’t really apply anymore.

The question becomes: What is a designer responsible for now? What are they capable of?”

Zhang has seen the field of design become increasingly standardized over the years, even as the tools have become more accessible. “There was a time when being a good designer meant polished presentations, great communication, and pixel-perfect execution. Now, you also need to be able to build, test, and explore ideas quickly.”

That shift, she believes, creates opportunity. “Newcomers can compete with incumbents more effectively than ever,” she says. “They come in with fresh eyes and fewer preconceptions. AI can level the playing field.”

Designing the Future of Design Education

Still, Zhang acknowledges the inherent challenge for institutions. “If the tools are changing so quickly, how do you even write a curriculum?” she asks. “Maybe you don’t. Maybe instead, you model what it means to keep learning. You create space for experimentation. You show students how to ask better questions.”